Came across an interesting article, The Origins of Sprawl over at The Paris Review. Have to admit, it didn’t end up where I thought it would.

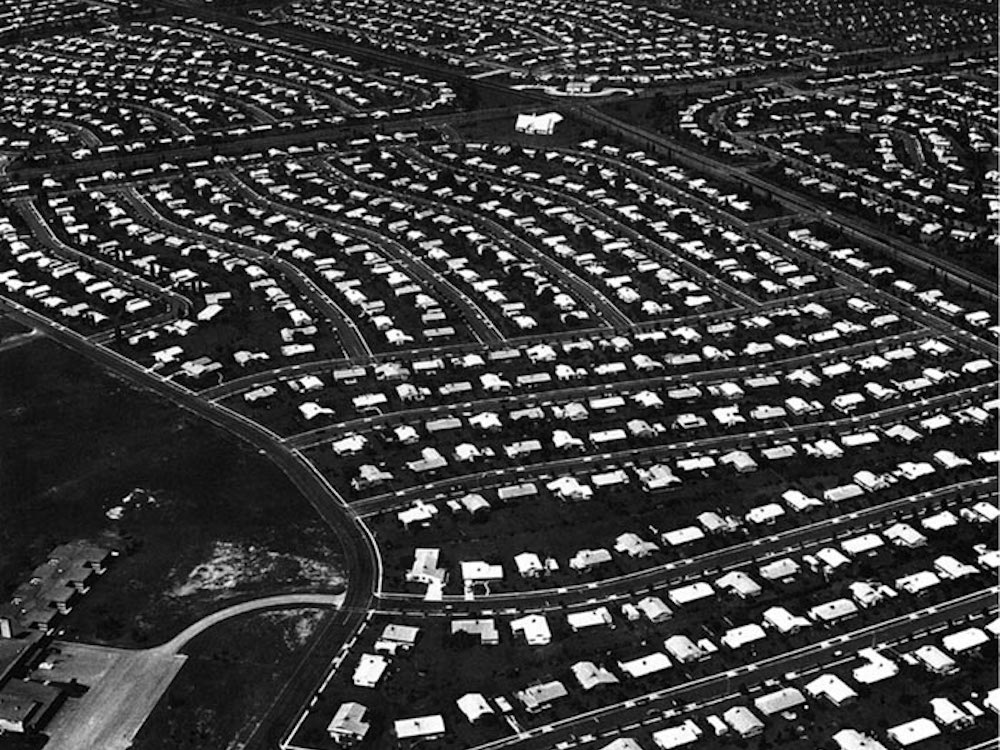

It’s suburban sprawl, yes, but Levittown also calls to mind what the architect Rem Koolhaas dubs “junkspace”—ugly, bland, utilitarian buildings and a lot of things that serve very little purpose. “Junkspace is the sum total of our current achievement,” Koolhaas writes. “We have built more than all previous generations put together.” The buildings I see in Levittown and many other suburbs are often just that, buildings. They serve little purpose other than to house things, with little thought put into the design; it’s all function over form.

To Koolhaas, the traffic is junkspace, the little stores are junkspace, and, in a very Gibson-esqe way, he believes that, someday soon, “Junkspace will assume responsibility for pleasure and religion, exposure and intimacy, public life and privacy.”

It seems sadly ironic that what was initially considered ‘modern and revolutionary’ is now considered by some to be ‘junkspace’ and ultimately was a system that contributed to the oppression of people of color.

Around the same time as the glowing reports of William Levitt’s vision, the real legacy of Levittown started to take shape, the one that, like the fence maintenance, was meant to keep it as white as possible: clause 25 of the houses’ leases, which banned occupancy “by any person other than members of the Caucasian race” save for “domestic servants,” was taken out after a group called the Committee to End Discrimination fought to have it removed. They were successful in having the clause taken out, but Levitt didn’t change his policies regarding whom he’d sell or lease to, saying, “The plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities.”

The Levittown color barrier wasn’t broken until 1957, when residents in the second Levittown, outside Philadelphia, arranged a private sale of a home to Daisy and Bill Myers, an African American couple. In a picture from the family’s move-in day, August 13, 1957, you see the remnants of a mob that tried to protest their arrival on Deepgreen Lane—about twenty-five white people surround the house, which a couple of police officers guarded as the family tried to settle in. Some would argue that Levitt was just bound by his times, that federally sponsored acts like “redlining,” which began with the National Housing Act of 1934 and kept African Americans from living in mostly white areas, were in place before the first white fence. Levitt himself would defend his decision, writing once, “The Negroes in America are trying to do in 400 years what the Jews in the world have not wholly accomplished in 600 years,” going on to say, “as a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. This is their attitude, not ours.” Of course, what Levitt left out was that he and his family had built an even more exclusive—and exclusionary—community in the Long Island town of Manhasset.

Perhaps the one standout thing of many I have learned as a result of BLM and the civil unrest in the US is how oblivious I have been to how racism has been baked into most aspects of the North American society I grew up in. Seems every day I discover another thread.