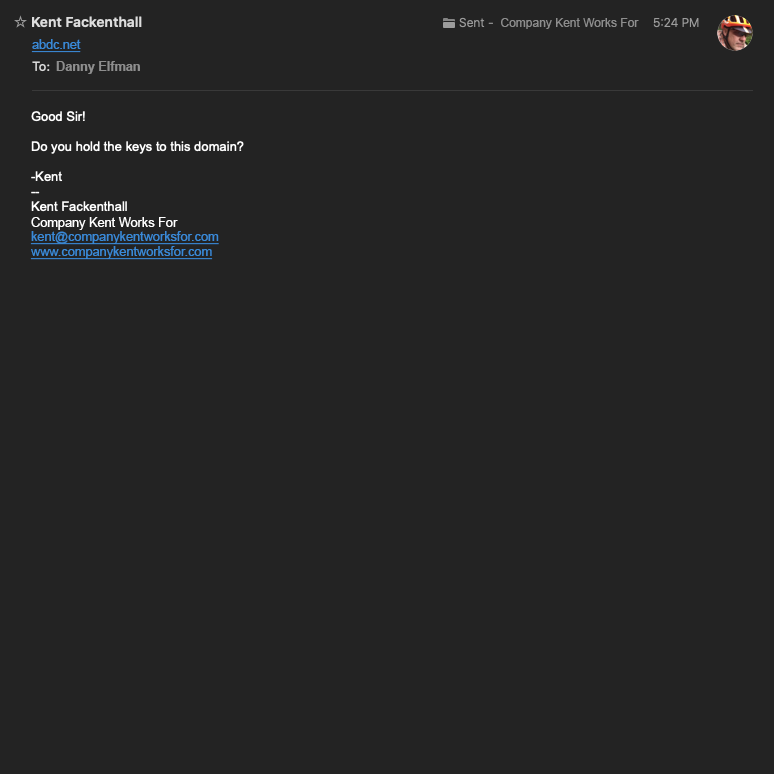

Just sent this email to my ‘web guy*’:

And I thought, “I’m in the medieval digital age.”

*names have been changed to protect the innocent

Just sent this email to my ‘web guy*’:

And I thought, “I’m in the medieval digital age.”

*names have been changed to protect the innocent

I was reading William B. Irvine’s A Guide To The Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy and he talks about developing one’s ‘philosophy of life.’

I think mine might be Always Be Processing Gear.